Cancer Research Spotlight: Curtis Thorne, PhD

The Thorne Lab: curing colorectal cancer through a microscope

When it comes to colorectal cancer, University of Arizona Cancer Center member Curtis Thorne, PhD, and a multidisciplinary team are on the precipice of a burgeoning discovery that can improve targeted therapies and advance precision cancer care.

The team includes Thorne, who is an associate professor in the UArizona Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine; Cancer Center member Aaron Scott, MD, a medical oncologist and associate professor in UArizona Department of Medicine; and Cancer Center member Christopher Hulme, PhD, a professor in the UArizona Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology. Last year, they won a funding award at the Trends Gala for their work “Novel Silver Bullet Therapy for Colon Cancers and Beyond” through the Trends Charitable Fund.

“Together, we're working on this novel therapeutic that can simultaneously target three different cancer-causing enzymes that we think will be a very effective anti-cancer therapeutic,” Dr. Thorne said. “The Trends funding was really critical because this is a high risk, high reward sort of project.”

The researchers have already been working for more than two years with international researchers to uncover the compound called DYR747 that targets vulnerabilities in colorectal cancer. They synthesized and tested more than 300 derivatives of their compound to optimize its accuracy, strength, and tumor-shrinking effectiveness.

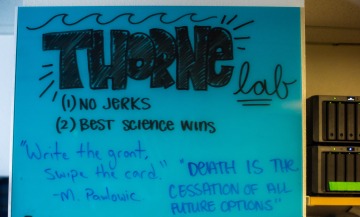

Creating an effective work environment

For Dr. Thorne and his team, developing cures for colorectal cancer is what drives them into the lab and beyond the current scientific cancer limits.

“In the Thorne Lab, we focus on the fundamental biology of the lining of the gut, as well as what goes wrong in that tissue to cause colon cancer,” Dr. Thorne said.

Dr. Thorne said his lab focuses on three areas: normal tissue homeostasis, how the lining of the intestine repairs itself when damaged, and early cell signaling events that cause tumor formation.

“In the end, we use all of those tools and all of that knowledge to discover new therapeutics to target colorectal cancer,” he said.

Focusing on the future

Despite Dr. Thorne’s success in cancer research, his career path veered far from the disease. His brothers had cancer when he was young, and he did not want to be near hospitals.

“I came to cancer research kicking and screaming,” he said. “I initially entered grad school wanting to be a botanist.”

His resistance transformed one day through the life-altering event of his own cancer diagnosis during his postdoctoral fellowship.

“I found myself working in the lab on the 11th floor, and then I would go down the elevator to the chemo room on the second floor and get chemotherapy put into my veins. It had a dramatic physical effect on me. That is something I have never forgotten,” he said.

“I have tremendous gratitude for the scientists three decades earlier who discovered the chemo that essentially cured me,” Dr. Thorne said. “I realized I myself have the ability to play a role in that.”

He said his personal cancer experience impacts his daily decision-making for what his lab does, the direction they go, and the impact they can have on cancer. Consequently, Dr. Thorne said he has been very deliberate in building an enthusiastic, hardworking team.

“All the people in my group, whether we have research assistant professors or graduate students or postdocs, they're all in on science, they're all in on discovery, and they're all in on making an impact on cancer,” Dr. Thorne said. “For that reason, we're an energetic group, we're lively, and we hold each other to high standards–all with the goal that we publish great science and that we really make an impact on the patients.”

He said working at a comprehensive cancer center, that has both bench scientists and clinicians in the same building with a broad spectrum of expertise, allows their multidisciplinary team to attend seminars together, meet often, and write grants and papers.

“It's the way modern science is done,” he said. “As a basic scientist, it is easy to be in the lab and lose sight of the real clinical challenges, but here at the Cancer Center, the physicians are right down one floor, and I meet with them routinely. I hear their daily stories of the challenges they are dealing with in the clinic. That informs the kind of science we do to meet those challenges more appropriately.”

He said that a crucial element of his UArizona Cancer Center membership is that it is part of a large nationwide network of comprehensive cancer centers that are talking to each other and sharing information, protocols and newly discovered therapies.

He said that one thing he hopes the team members who train in his lab take with them in the future is their enthusiasm as a group.

“Sometimes studying disease, making progress is terribly slow. It can be demoralizing. But what we do here, it is a great honor to be in a lab, to do these kinds of experiments, to do something positive for the world and something positive to ease pain and suffering,” Dr. Thorne said. “For that reason, we are optimistic people. And I hope my trainees take that to wherever they go next—that optimism towards the impact that they can make.”